Resources

A primer on CMS

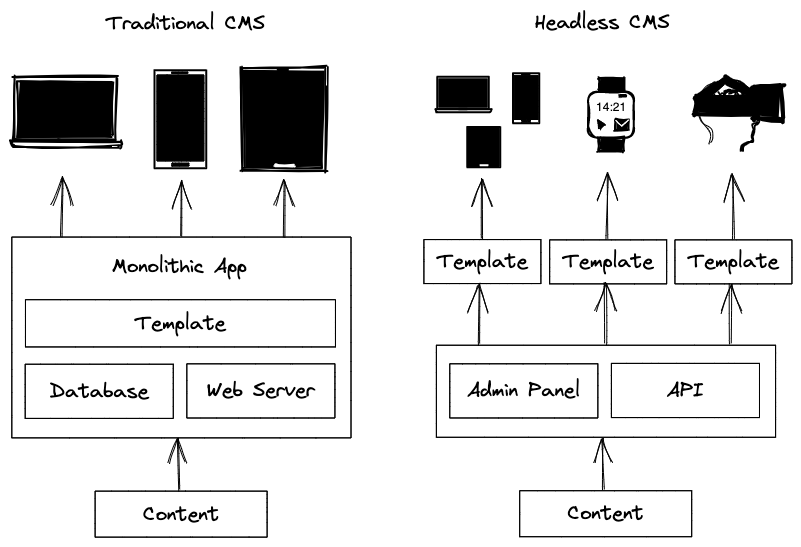

If you create content for the web, then you've probably had some experience with content management systems (CMS). Most sites that receive regular updates will have:

- A hidden interface you can access to publish content

- A database that stores that content

These two bits i.e. the admin panel, are together referred to as the 'body', whereas the place someone may go to view the content publicly i.e. the website is referred to as the 'head'. Historically, these have been coupled together in a single software solution for ease-of-use, and there's an entire landscape of website builders and hosting plans that package it all together, vying for your attention.

An emerging category of CMS is the 'headless' one, where there's no 'head' included. There's still an interface for managing content, but that content is provided via APIs for developers to query and build applications with - there may be many 'heads'. They generally provide greater freedom at the cost of increased technical complexity - you'll have to create your own data structures, and probably build your front-ends from scratch.

If you're unsure why that might be desirable, keep reading - otherwise, skip to reading about why I've chosen Payload specifically for this site.

As always with web development, the terminology is wishy-washy

The benefits of designing your own data

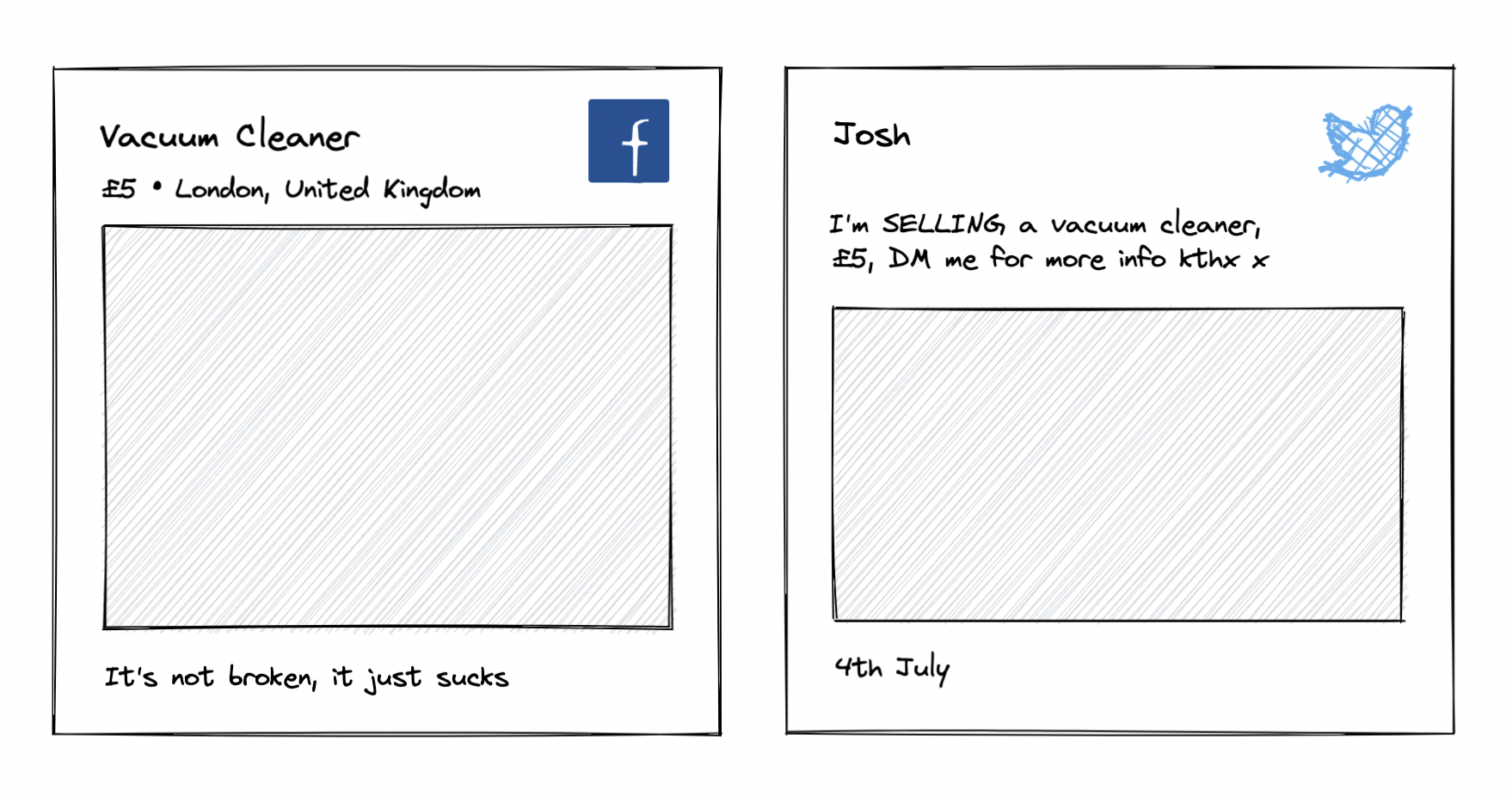

If you use any kind of social media, then you already know that the people behind Facebook and Twitter have made decisions about the 'shape' of the content to keep it in-fitting with their vision for the design of their websites.

At a high level, both platforms provide the ability to create posts that may contain text and images published at a specific time. Digging into their discrepancies, Tweets may have characters limits and hashtags, whereas Facebook posts may have specific privacy settings and activities attached to them. If you're looking to start a blog or run a business, then the constraints of each platform will inform their compatibility with you - I use Tumblr as the platform for posting my hobbyist photography because it suits my desire to create simple pictorial posts with titles, and provides a customizable theme for others to view them.

When we learn a new paradigm in technology, like what a typical 'post' is, we often assume it is the best design in the present once it makes sense to us because it is the only one that exists - if you're out having a nice meal, it might occur to you that you could post a photo with a geolocation to Facebook, because you've seen those features used before. It's easy to forget that there are people deciding how this all works, and that they can and do experiment over time with what a post actually is. Large platforms strive to provide generic enough features to accommodate as many use cases as they can, but if you were in control, would you want more or less specificity?

For example, somebody selling a used vacuum cleaner on Ebay may be presented with an input field dedicated to describing the item's condition, which will ultimately get its own dedicated space on the listing's webpage. The same post to Facebook may simply see the item's condition tacked onto the end of the post body if the seller even remembers to include it. If you consider that Ebay is not just a 'website', but also an 'app', and that your local Facebook marketplace could also potentially be delivered as a weekly print magazine, then you come to understand that while the context in which the data is presented is important, the driving force of the internet has always been the data itself.

Imagine if you got to decide what that data looked like for your application - if you didn't have to call it a 'post' if that didn't suit you, if you kept a hold of it yourself instead of submitting it to be stored by somebody else. Imagine having that freedom, without having to code it from scratch. This is where a self-hosted, headless CMS like Payload comes in.

Consider how a Facebook marketplace post differs from an Instagram post, and how that forces people to think outside of the box depending on how they're using each

Case study

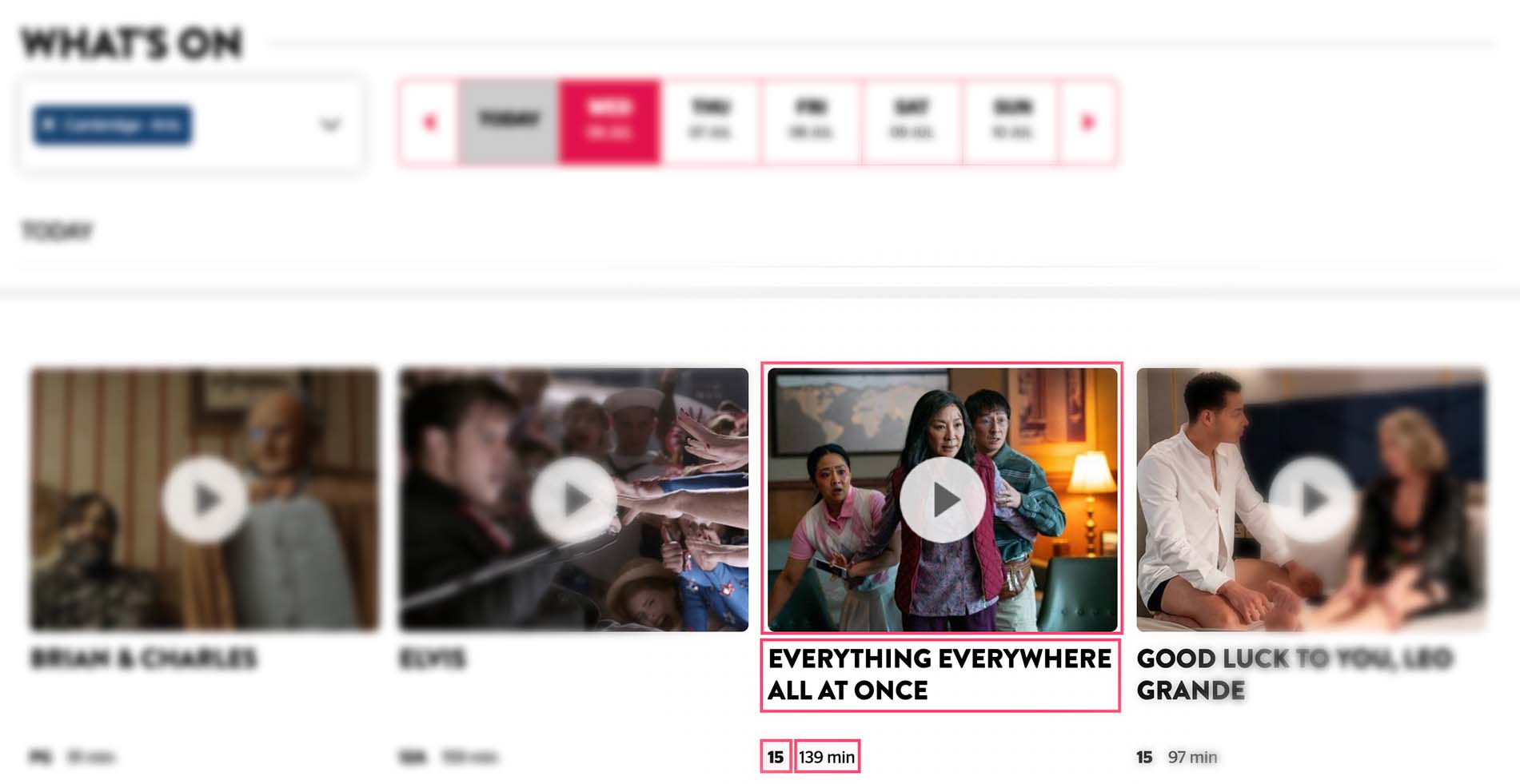

Another example of this could be showtimes for a cinema. Imagine you have both a website and digital signage outside the venue, with both needing to display information about the current films. You could make two 'heads' - one website for the browser, and another kind of view to load onto the digital sign outside. As long as they were both internet-connected, they could both retrieve information from your headless CMS via a REST API e.g. https://mycinema.com/api/films where each 'film' consists of:

- A title

- A runtime in minutes

- A promotional image

- A brief synopsis

It would be plenty of work to build such a system from scratch in a way that would accommodate non-tech-savvy authors, and there's no free out-of-the-box solution available online for this specific use case.

A headless CMS allows a web developer to define what a unit of 'film' data is, and provide authors with a clean interface to publish films to the system.

Dissecting the user interface of the showtimes page from the Picturehouse Cinemas company shows film posts comprise of at least a name, trailer, MPA rating and runtime

What if you took that principle of data design a step further, and allowed authors to control more aspects of the end applications - for example, the style and layouts of websites?

This is the unique selling point of website builders like SquareSpace and Wix. They define blocks of content, such as text, image galleries, videos etc., and allow authors to create pages made up of any number of these blocks in any order. Each of these blocks may have extra properties dictating their style, such as color and background images, again to be obeyed by the developer of the 'head' applications as they see fit.

This can be achieved in a headless CMS that allows for creating your own data structures. Instead of 'films', the concept of a 'page' could be created, comprised of similar blocks of content. Theoretically, authors could build entire websites of pages and posts with unique combinations of these blocks, so long as the user experience was accommodating.

Why Payload?

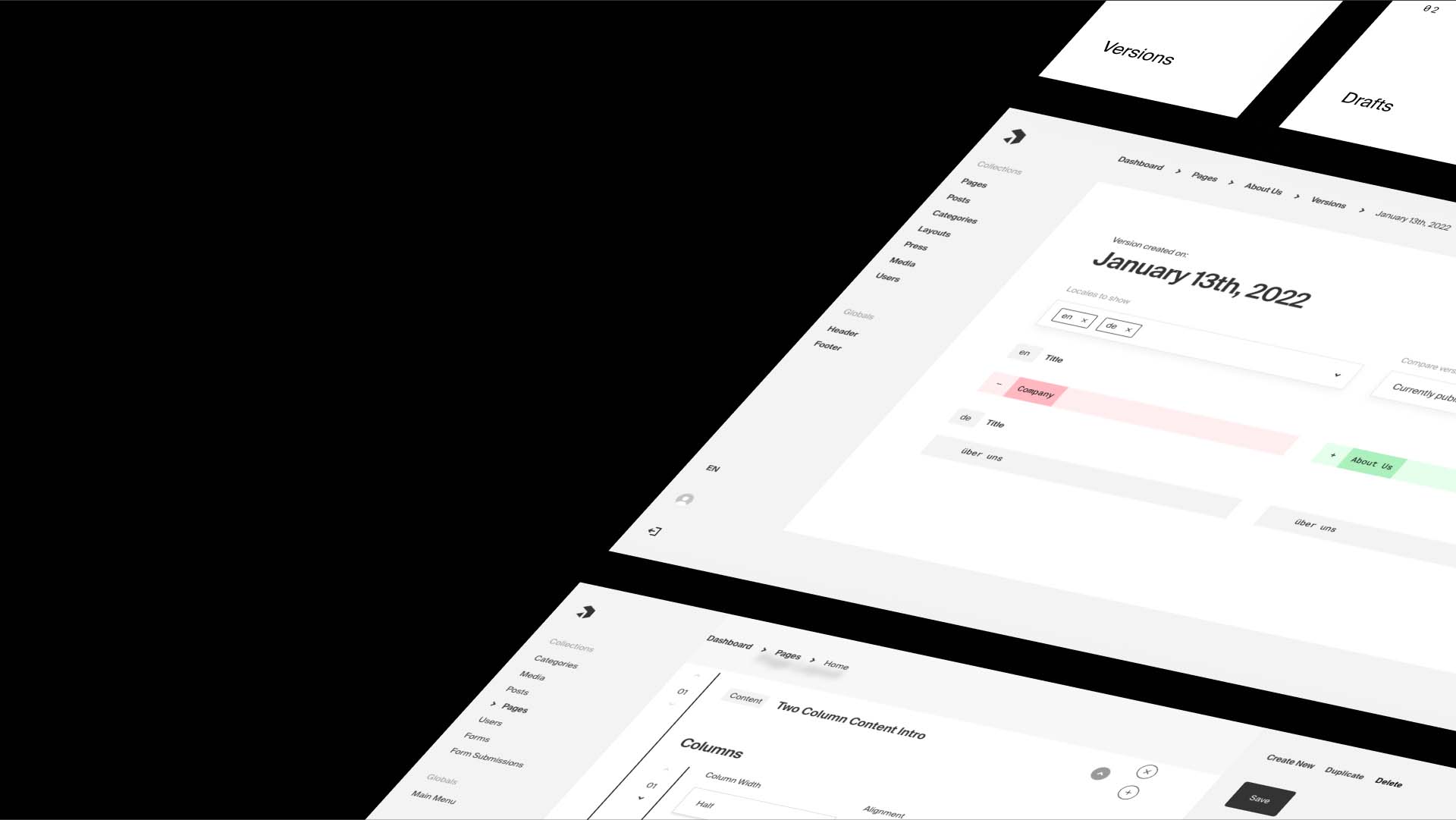

I made this website using React and Payload CMS. I'd previously used Wordpress, but grew tired of keeping it up to date for the sake of features I wasn't using; I wanted something simpler, and I wanted more control over the shape of the data.

Throughout this process, I catalogued my experiences into pros and cons. Payload is new, and still has teething issues, but I'm comfortable saying that it's the best CMS system I've ever used - one I'd never found the time to make for myself. This isn't a sponsored post, but I'll happily evangelize the ethos the makers TRBL display through their enthusiastic approach to work and knowledge sharing.

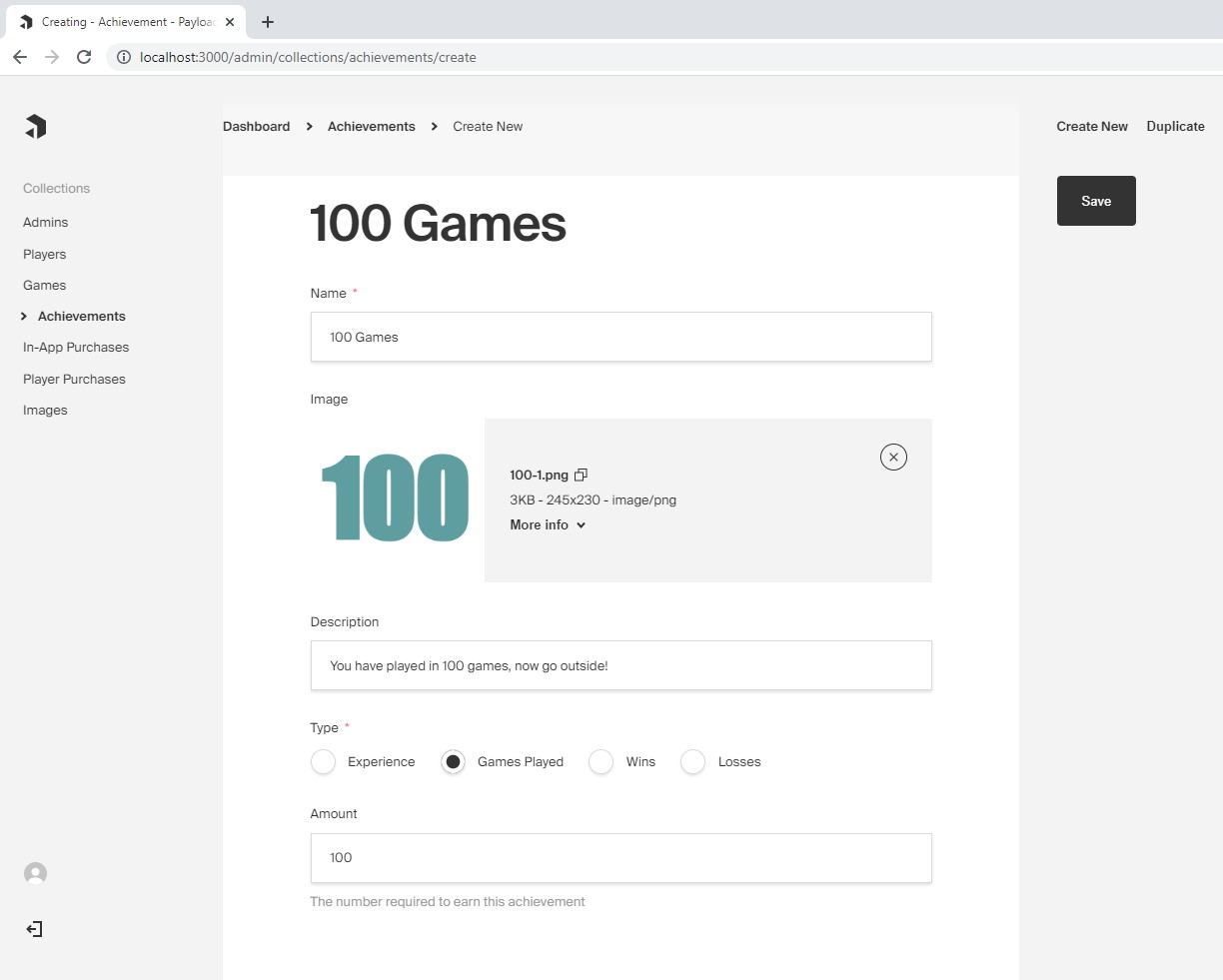

The Payload admin panel being used to create achievements for a video game

Pros for Payload

"Free forever"

It's here that Payload is best-in-class - even if the software goes in a direction I end up not liking, there will always be capable snapshots of the framework on NPM; the work has already been done, and open-sourced. Additionally, since self-hosting doesn't preclude a managed solution, there will also be guides and one-click-deploy solutions out there to help take it live. It's not prescriptive, and can be hosted in isolation - depending on your architecture, you can even use the Payload library to call directly into the database, bypassing the need to make HTTP requests to the REST API.

The icing on the cake is that the developers are active on Github, and engage with the community to share knowledge of their own professional, client-oriented development practices from their experience operating as a digital agency.

Clean & data driven

Although it takes some learning, defining your own data schema means you never have any more features than you need. This allows the admin interface to remain clean and customisable, with a small footprint - it's not 'overkill' to set up for any given project that needs some dynamic data, and the form libraries being used make for pleasant editing experience.

Uses standard technology

Payload is written in TypeScript, and the admin panel is made using React. Aside from being popular technologies, aligning yourself with them allows you to share your code between your own Payload configuration, and any of your front-ends. There's little mysticism, which means you've got greater agency if you need to hack your way to a solution (something I needed to do as an early adopter to skirt around some bugs).

Cons

New and shiny

Aside from a few technical issues to be expected with the launch of a new software product, my concerns regarding Payload are largely rooted in time and circumstance.

As with everything, new software is prone to bugs, breaking changes and a lead-time-to-community resulting in an absence of self-service support (via Google). This is emphasized when comparing Payload to Contentful, its closest contemporary, where the community has been building out plugins for years. With Payload, more complex behaviours are left to you, meaning it's not an all-in-one solution. This necessitates a more technical knowledge, whereas other solutions allow non-technical people to create and maintain websites.

Since release, they've incorporated a few ubiquitous features, such as 'draft' post states, change diff-ing, and hooks for common operations. In regards to feature requests, I'm unsure how far the developers want to go in any specific direction before the system itself would be considered bloated. To spur adoption, Payload may benefit from a clear and communicated public roadmap.

Lack of content migration

If you change the data schema in a breaking way, Payload cannot reconcile what is already there - e.g. changing the type of a field with data already in the database. Since it's already opinionated about the type of database to use, the system itself may benefit from including some aspects of database management 'for free'.

Teething issues

I've experienced a number of bugs with the admin panel that have resulted in some lost work (data not saving, UI elements relocating about the page, irreconcilable time-outs…).

In general, I think their library could produce more descriptive error messages, and their online documentation could be more thorough.

Taking the plunge

Having worked as a web developer for years now, I find Payload to be quite refreshing - its versatility lends itself well to more esoteric and interesting projects that require bespoke content models. I work in the games industry, and I could see Payload underpinning everything from patch notes to an in-game store - in fact, they recently published a blog post about this very thing.

At the very least, I'll certainly be keeping an optimistic eye on it over the next year, and greedily integrating and subsuming each new feature into this site.