A puzzling topic

Without pressure, life slows down. In otherwise action-packed video games, puzzles are unmasked as chores waiting idly for you to complete them, which can kill the pacing even if the puzzle in isolation is well-designed. Without pressure, a player mightn’t even pause the game when their doorbell chimes, leaving their character in an existential, Wreck-it-Ralphian limbo while the background music fades and loops. Awkward, if they were supposed to be saving the world.

Pressure is a topmost concept. An active type of challenge, it creates tension, contributes to difficulty, and can produce anxiety and adrenaline. Like salt in a recipe, used well it can mellow out bitterness and enhance sweetness; used poorly it can give you a heart attack or leave you feeling... salty.

In Uncharted, periods of forced downtime see players go from swinging around cliffs and intense firefights to quietly traipsing back-and-forth between dark rooms pushing buttons

Just in time?

Famously, diamonds are created from pressure and time. In video games, however, time-sensitive tasks can be a lazy way of applying pressure. Players crave diverse new experiences, so developers looking to utilise time pressure have had to invent new ways to push players through their hoops.

Let’s consider one of the most pressure-oriented experiences in modern gaming: the battle royale. Generally, a large group of disparate players enter into a large combat arena that shrinks in size as fighting occurs, with the goal being to eliminate other players to become the last remaining team. In source material, shrinking the play area is a method of ensuring the game will eventually draw to a close should the players hide, get lost, or embrace pacifism. In their own arms-race to capture our attentions, developers have since stacked additional and increasingly complex mechanics on top of this model, resulting in many observable sources of pressure in a given game:

- Pressure to loot the best equipment

- Pressure to eliminate other players

- Pressure to not be eliminated by other players or environmental hazards

- Pressure to complete additional achievements (battle-pass rewards)

- (Optionally) Pressure to entertain an audience while playing

Vampire: The Masquerade Bloodhunt uses irregularly shaped safe zones and clusters of hostile AI to pressure players into rerouting

This means, for a game with guns, the qualities of a good player have as much to do with communication, time management and orienteering as being a sharp-shooter. These pressures translate into requirements like understanding how the server will spawn resources or alter the map, and staying abreast of time and enemy positions – additional strains on players’ cognition that are intensified by each other when they overlap.

One of the most interesting feed-back loops we can exploit here is the dynamism of games. If the play area is altered automatically based on players’ actions, then we end up in a situation where players influence the world, which influences the players, which influences the world…

A world of pressure

In PvP games, the matchmaking system sets the strongest precedent for pressure – if you’re pitted against seasoned professionals, they’re going to be able to apply pressure to you more effectively than a roster of newbies, regardless of the game's mechanics.

While Deep Rock invokes tired design paradigms like defending moving vehicles and base stations for set periods of time, the need to re-stock in-between combat forces a parallelization of efforts that pressures players into effective teamwork

In PvE games however, we have more control as designers to dictate the game’s events. My favourite example of this is Deep Rock Galactic, a sci-fi game about spelunking dwarves. While mining resources, an AI director spawns waves of mutant bugs to disrupt your progress. It’s a simple concept that works well because the system is context aware – like Left 4 Dead, the game will punish complacency, but reward you with a reprieve if you successfully fight back a wave of enemies. Constantly flitting between modes of mining and fighting keeps you engaged and alert, and provides enough variance to stave off boredom on repeat missions. With the right tuning, AI can give a game a satisfying ebb and flow, up until the player wants to pause the action.

Controlling the pressure

I believe players should be able to pause the action. We should be mindful of boundaries as designers – we’re making something we want people to enjoy, not hold them hostage. A player should be invited to exert themselves, but be provided with an excuse should they fail - they may feel stupid for failing a level in a game with low-pressure, but better for having given a more difficult game “a good go”.

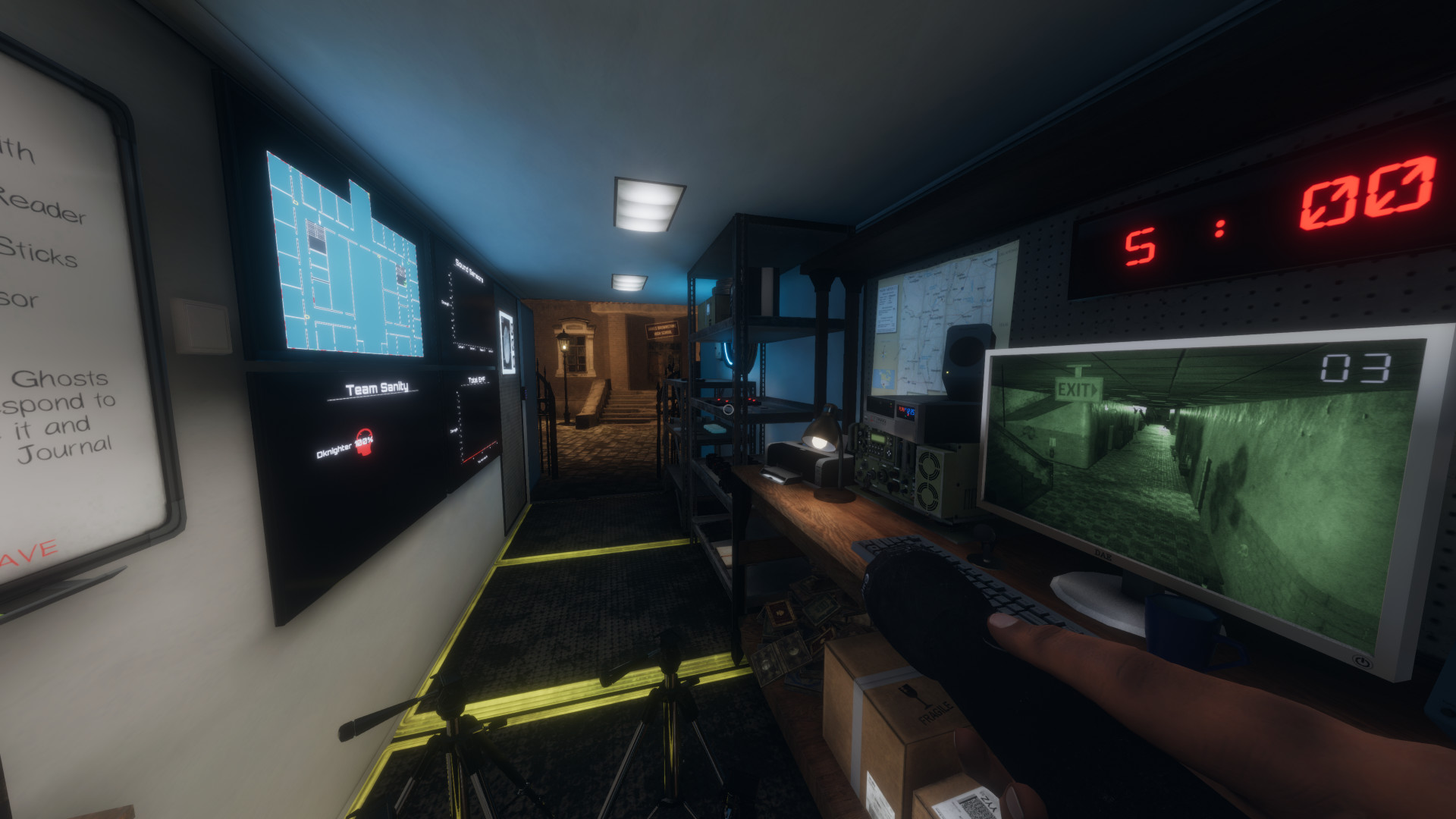

Horror games such as Phasmophobia and Pacify allow you to opt-in to pressure – players willingly submit to entering a scary environment, but can retreat back to the outside of their respective haunted houses (with some checks and balances…)

Both Apex: Legends and Vampire: The Masquerade Bloodhunt provide players with systems to mitigate punishment when under pressure, e.g. consumables that grant immunity to environmental hazards, and the ability to mark and drop equipment for teammates, revive them. Deep Rock Galactic missions, like the treasure rooms in Sea of Thieves, contain a finite number of resources, meaning while there isn't a discrete time limit, the level of risk increases the longer players decide to hold out (just don't lose your hat, Indy!).

In that vein, pressure needn’t be limited to time; it boils down to coaxing the player into giving a good performance in exchange for a reward. Applying pressure to an inherently uninteresting mechanic is an unjust punishment that will only cause frustration.

There are consequences

Punishment is a divergent topic, but it’s useful to understand that for pressure to work, you may also need a consequence for failure. Good games exist delicately, neither too-hard nor too-easy, but with no challenge, there’s (arguably) no reward.

Even a mechanically bereft, linear game invites the player to challenge themselves mentally – to engross themselves in it so far as to complete it, failure being to quit.

A casual mobile puzzle game like Crayon Physics still presents a challenge, but there's no real pressure to succeed by design, and little punishment to match; it's relaxing, and ergo has the right level of pressure to succeed in its goals.

Take the trend of 'parkour' platforming levels in games like Minecraft and Roblox, made simply using in-game editors: the higher you climb, the more pressure you feel to not plummet to your death. It's a concept that needs little explaining because it maps 1:1 with the real world, is more interesting the more times you almost fail on the way to success, and more frustrating the more times you become stuck on a difficult jump (could you provide more checkpoints and alternate routes?).

Some games reel back player progress, while others alter the world permanently to remind the player of their mistakes. In some games, a lack of punishment is the reward: “I didn’t fail, so I get to move on to the next level”.

This is yet another thing that needs balancing – imagine if a battle royale booted you straight back to the main menu without fanfare after winning a game.

In Terry Cavanagh's Roblox level 'Climb the Giant Man Obby', the player, driven by the mystery of what lies at the top, is invited to scale an obstacle course shaped like a giant character with carefully timed jumps

Pressure needs a release

The need to expunge pressure is apparent when considering that wildly successful games with esports communities see high-profile players ‘burn out’. High-pressure, while fun, can lead to fatigue, and limit repeat sessions. A rollercoaster going at a constant slow speed would be boring, but a rollercoaster going at a constant high speed would be nauseating. Thinking of this as a tool as opposed to a caveat means we can plan content roll-out and opportune breaks in the action. The Warhammer series does this to great effect, expecting you to only complete one or two campaigns per session and returning you to a peaceful and ubiquitous social hub in-between, the prevailing tea-breaks between cliff-hanger endings.

An e-sports team celebrate a tournament win

If you find yourself frustrated at a section in an otherwise enjoyable game, identify sources and amounts of pressure and consider whether the experience would be improved by adding or removing them, changing their complexity, or allowing the player a level of control.

It might be the key to shifting your feelings from "ugh, it's finally over", to "whew, that was satisfying".